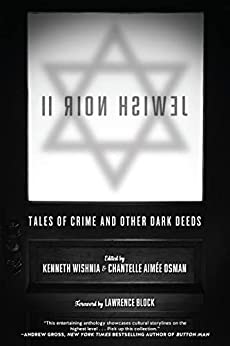

Just in time for the High Holidays, comes Jewish Noir II, edited by Kenneth Wishnia and Chantelle Aimée Osman. In his lively introduction, noted crime writer Lawrence Block says you can sum up every Jewish holiday in three sentences: “They tried to kill us. We survived. Let’s eat!” While great food is an essential part of Jewish holiday celebrations, Block points out that the first two sentence are even more tied to the Jewish experience and, as he says, make the combination of Jews and noir almost inevitable. And timely, I’d add, given current trends.

This collection of twenty-three short stories, many of which were written by prize-winning authors, are clustered in six themes: legacies, scattered and dispersed (stories from the diaspora); you shame us in front of the world (embarrassment and dishonor); the God of mercy; the God of vengeance; and American Splendor (stories that could only happen in the United States). Editors Wishnia and Osman point to a subtext of many of the stories: fear amidst the stresses of modern life. Fear of the past, fear of loss, fear of anti-Semitism, fear of violence. Fear that is another signpost on the road to noir. Even with that common thread, the stories themselves are wildly diverse, and readers will find many that appeal, regardless of stylistic preferences. This review tackles only three of them, from across the themes mentioned.

“Taking Names,” the opening story by Steven Wishnia, sits perfectly in the sweet spot between past and present. It begins with the commemoration of a notorious tragedy, the 1911 fire at New York City’s Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. In that calamity, scores of young women jumped nine stories to their deaths, rather than be burned alive. Because of the business owners’ negligence, 146 people—mainly Italian and Jewish immigrants—died. The issue of worker safety is brought up to the present day by reporter Charlie Purpelburg, who’s covering union efforts to increase worker safety in the construction industry. Once again, risky conditions affect the most vulnerable employees—undocumented workers, this time around. They’re not only caught in the political machinations of Jewish developers skirting safety regulations, their wages are being stolen. Enter the social media trolls. Where does all this racial hostility end? No place good.

Craig Faustus Buck’s “The Shabbes Goy” is another tale of exploitation, this time of an elderly woman by her ultra-religious husband, who fills their apartment with gloom and domination. How three members of the younger generation ally to thwart him is quite satisfying. Funny and horrifying, all at once.

“What was I thinking?” is the first line of “The Nazi in the Basement” by Rita Lakin. An elderly Jewish woman living in California returns to New York for a funeral and decides to do the unfathomable. She visits her old neighborhood in the Bronx for the first time in decades. When she lived there, the residents were mostly Jews, Irish, and Italians, and now, before she can park the rental car, she encounters teenagers from Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Hong Kong, and Bangladesh. They wheedle most of her life story out of her. But she doesn’t tell them the ending, the tragic events that produced in her “the scars masquerading as memories.”

Many of the remaining stories address the issues of younger generations of Jews and people living in other countries. Still, it is today’s elderly, grandchildren of the immigrants from the last century who have witnessed the massive social changes of upward mobility, and who, at this point, may be most caught between past and present.

By Don Winslow, narrated by Dion Graham – For a while yet, perhaps every gritty, noir cop story set in urban America will be compared with the television series The Wire in terms of realism, character development, and sheer storytelling power. (Dion Graham, who narrates the audio version of Don Winslow’s much-anticipated new cop tale played a state’s attorney in that series.)

By Don Winslow, narrated by Dion Graham – For a while yet, perhaps every gritty, noir cop story set in urban America will be compared with the television series The Wire in terms of realism, character development, and sheer storytelling power. (Dion Graham, who narrates the audio version of Don Winslow’s much-anticipated new cop tale played a state’s attorney in that series.)

By Donald Ray Pollock — In the early 20th century, the three Jewett brothers are under the thumb of their crazily religious, impoverished failure of a father. He’s working them practically to death in the swampy field they’re clearing near the Georgia-Alabama border. The wealthy landowner has promised that if they meet some impossible deadline, he will give them 10 laying hens. If so, maybe they will finally have something to eat. What the reader knows is he has no intention of keeping that promise.

By Donald Ray Pollock — In the early 20th century, the three Jewett brothers are under the thumb of their crazily religious, impoverished failure of a father. He’s working them practically to death in the swampy field they’re clearing near the Georgia-Alabama border. The wealthy landowner has promised that if they meet some impossible deadline, he will give them 10 laying hens. If so, maybe they will finally have something to eat. What the reader knows is he has no intention of keeping that promise.