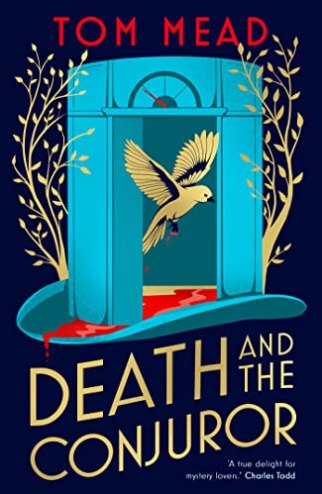

Fans of locked-room mysteries should love debut author Tom Mead’s historical mystery, Death and the Conjuror. In 1936 London, elderly showman and conjuror Joseph Spector is called on to aid Scotland Yard detective George Flint, who hopes Spector’s skills at misdirection can lead him to figure out what really happened in a strange case that involves not one, but two locked-room murders.

German immigrant (sometimes referred to as a psychologist and sometimes as a psychiatrist) Dr. Anselm Rees has recently relocated to London, along with his daughter, Dr. Lidia Rees.(Mead wisely set the story a few years before the gathering war clouds would have further complicated the story.) The elder Dr. Rees has gradually acquired three patients—musician Floyd Stenhouse, actor Della Cookson, and author Claude Weaver.

Lidia and her playboy boyfriend Marcus Bowman arrive home late one night and learn Dr. Rees’s throat has been slit. For one reason and another, all three patients become suspects, along with an unidentified evening caller, daughter Lidia (who stands to inherit), and her boyfriend (who needs the money). The door to the office was locked that evening, as were the French windows, with their keys on the inside.

On the evening of another unproductive day of investigation, Flint receives an urgent call from the musician Stenhouse, who believes he’s being followed. Flint and his sergeant hear a shot, and fruitlessly chase a shadowy figure. Upon returning to the apartment building, they discover the second locked-room puzzle: the elevator operator is dead inside his small cage.

Although Spector provides occasional interesting disquisitions about the creation of illusions, his potential seemed not fully exploited. Stories about illusionists and (real-life) magicians usually include some spectacular demonstrations. In this story, inexorable logic wins out. Because the setup of the two murders was so complicated, many pages are required to explain them, as various theories are posed and discarded.

You may have the sense—despite the automobiles, hairstyles, and a few other signals—that this story could just have easily taken place fifty years earlier, given the dialog, the background narration, and many of the characters’ attitudes. It has a definite old-fashioned feel, which, on one hand, is part of its charm, and on the other, may distance you from engaging with the characters.

It is a locked-room puzzle in that fine tradition, with a surfeit of clues, red herrings, and suspicions. The clever and complicated plots the unknown antagonist concocts will likely keep you guessing all the way through.

Locked room mysteries are always fun to read, but my favorite still remains “The Adventure of the Speckled Band,” which thrilled me in my youth. It was my introduction to Sherlock Holmes.

And I think it’s the only one I remember how it ends! Except Hound of the Baskervilles, which I’ve seen on stage numerous times!