Dan Smith, creative commons license

At a time when the U.S. Senate is considering a new member of the Supreme Court, the wisdom of viewing today’s problems and challenges through a 250-year-old lens is once again under scrutiny. No words put on paper today are likely to have as long and as consequential a tail for Americans as the Constitution of the United States.

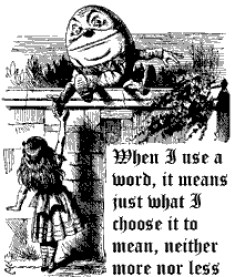

In this month’s Language Lounge for Visual Thesaurus, linguistic provocateur Orin Hargraves returns to Independence Hall to consider the Founding Fathers’ accomplishment. In contrast to the typically fleeting nature of oral pronouncements (perhaps of the kind delivered in Senate hearings), Hargraves says, written language can have a “practically unlimited” afterlife. At the same time, it has weaknesses. It is missing context (quill pens versus the Internet) and, in the case of something written in the 1700s, people of today—our Senators, for example—cannot query the Founding Fathers for clarification and relevance.

Hargraves says the Constitution’s drafters of significant documents, like the U.S. Constitution, are aware “that the force of their words will long outlive them.” As a result, they choose those words with extreme care and provide a way to alter and update it, not easily though. Our Constitution now has 27 Amendments.

Despite the founders’ care, debate over the context and meaning of some of the Constitution’s provisions, especially the Second Amendment, is virulent. Even within such a presumably sedate setting as the Language Lounge, Hargraves says, past posts on this topic have inspired reader rants requiring “editorial intervention” by the Language Lounge masters. The prospects for consensus on a range of divisive topics seems remote, and The Washington Post says the first day of Kavanaugh’s hearings provided “a world-class display of bickering across party lines.”

One helpful resource ought to be the Corpus of Founding Era American English, based on some 100 million words of text from 1760 to 1799 from various sources. (See how one source suggests this body of work should inform the Supreme Court nomination hearings of Judge Kavanaugh.) Yet, a historical perspective on the meaning of language in the late 1700s may not satisfy partisans “deeply invested in one view or the other,” Hargraves says. I suspect he’s correct. However much the advocates claim their interpretations are based on long-ago principles, in fact they serve current interests.

One helpful resource ought to be the Corpus of Founding Era American English, based on some 100 million words of text from 1760 to 1799 from various sources. (See how one source suggests this body of work should inform the Supreme Court nomination hearings of Judge Kavanaugh.) Yet, a historical perspective on the meaning of language in the late 1700s may not satisfy partisans “deeply invested in one view or the other,” Hargraves says. I suspect he’s correct. However much the advocates claim their interpretations are based on long-ago principles, in fact they serve current interests.

While no one would insist on using an owner’s manual for a Model T Ford to repair their Fusion Hybrid, the Constitution is not given room to breathe and grow to serve society today. That was then. This is the uncomfortable now. Attempting to return to some earlier meaning (if we even were clear what that was) may be just another way to avoid doing the hard work of making our systems and even our brilliant Constitution work in the 21st century.