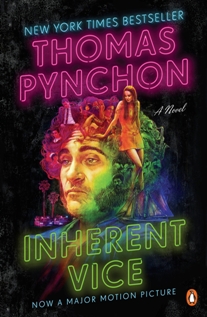

When this film (trailer) of a Thomas Pynchon novel was released in 2014, critics said it was undoubtedly the ONLY Pynchon book that could be corralled into a film. I’m a big Pychon fan—loved V, The Crying of Lot 49, and Mason & Dixon—but I started Gravity’s Rainbow three times and never got past page 100. So I can sympathize with the difficulties director Paul Thomas Anderson must have faced.

When this film (trailer) of a Thomas Pynchon novel was released in 2014, critics said it was undoubtedly the ONLY Pynchon book that could be corralled into a film. I’m a big Pychon fan—loved V, The Crying of Lot 49, and Mason & Dixon—but I started Gravity’s Rainbow three times and never got past page 100. So I can sympathize with the difficulties director Paul Thomas Anderson must have faced.

Joaquin Phoenix plays “Doc” Sportell, a private investigator subject to regular harassment from a police detective called Bigfoot (Josh Brolin). Doc’s ex-girlfriend Shasta has taken up with a wealthy married property developer, and the developer’s wife wants her to cooperate in a plot to institutionalize him so she and her new boyfriend can raid his bank account. Then the magnate disappears. Doc uses is slight investigative skills to search for both the developer and Shasta in a stoner’s 1970s Southern California.

This set-up takes you down colorful and unexpected byways, which I couldn’t possibly reconstruct, and a multitude of stars provide performance gems: Owen Wilson as a mixed up dude-dad, afraid to leave the drug cult that’s captured him; Hong Chau as the hilariously matter-of-fact operator of a kinky sex club; Martin Short as a cradle-robbing dentist, with his clinic in a building shaped like a golden fang; Golden Fang itself, a mysterious criminal operation that . . . None of this probably matters. Neo-Nazi biker gangs, yogic meditation, stoners. You just have to go with it. Joaquin Phoenix, understandably, displays about a zillion different ways of looking confused.

If you have a taste for the absurd and what Movie Talk’s Jason Best calls “freewheeling spirit,” this is definitely the movie for you! I try to guess whether audiences or critics will like a movie better. Right on the money this time: Rotten Tomatoes Critics Rating: 73%; audiences, 53%.