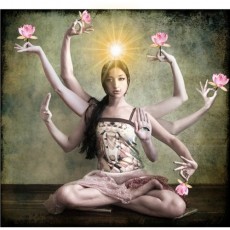

Iconic scene from “The Third Man,” based on Graham Greene’s novella.

When I used to hand out writing assignments to people, a question they always asked was “how long should it be?” I’m afraid my initial response wouldn’t be terribly helpful, and I’d say something like, “If it’s War and Peace, keep going; if it’s boring, a page is too much.” But then I’d end end with “Oh, about 15 pages, double-spaced. That’s all we have room for.”

In fiction, really, there are no similar space constraints; instead, “the dictates of the marketplace” set the limits. Literary magazines tell you what short story length they will accept. For novels, traditional publishers generally have a 90,000-100,000-word limit on what they will consider from an untried writer. Stephen King and Neal Stephenson and Thomas Pynchon can do as they please.

What I thought of as the final draft of my first novel came in at 135,000 words. I hadn’t given the total number a single thought. It was what it was. Fortunately, my good friend Sandra Beckwith (book publicist extraordinaire) caught me up short and directed me to several good websites (See The Swivet, or All Write – Fiction Advice) addressing the question of length. Before querying the first agent, I took electronic scalpel (also known as the delete key) in hand and cut characters, scenes, and dialog so that it now is a more svelte 99,000. Painful, but necessary, and I’m ever-grateful to Sandy for stopping me from embarrassing myself. In writing my second novel, I avoided some of the traps that led me into overwriting and finished the first draft at a slim-and-trim 70,000 words, which gives plenty of breathing room to enrich the story as needed during the revision stage.

For a while now, observers of the publishing scene have commented on the rising popularity of the novella—more than a short story in complexity and character development, less than a novel in plot twists and digressions. While novels today typically run 90-110,000 words, or about 300+ printed pages, acceptable lengths for novellas vary widely, anywhere from a long short story (10,000 words) to a short novel (70,000 words).

The popularity of these shorter forms is attributed to readers’ shrinking attention span; publishers’ reluctance to invest in producing an expensive book that isn’t a guaranteed best-seller; and reading habits, with Kindle, Nook, and even smartphones lending themselves to presenting shorter works. “Readers aren’t as aware of page count in the electronic realm as they are in a paper book,” says author Jeff Noon in a recent Forbes story by Suw Charman-Anderson. Kindle Singles are an example, and their inventory includes short fiction by best-selling writers.

Novellas also are less demanding on the authors who write them. A novel “is a huge emotional investment, and it can be risky to put all your creative eggs in one basket if things go wrong,” Charman-Anderson says, yet novellas let authors practice plotting and character development and develop their voice. And they provide the joy of actually finishing something. For self-publishers, they are a boon.

Let’s face it: some plots and some ideas just don’t lend themselves to longer formats. Cut the flab and you have a more compelling read. Some of the most focused and powerful English-language storytelling has been via the novella, and an illustration of their strength is how easily they have lent themselves to dramatization and our continued attention, starting with the grandmum of them all:

- The Mousetrap – Agatha Christie – 1952. She didn’t want publication to take away from the popularity of the theatrical version, so stipulated the novella couldn’t be published in the U.K. as long as the play was running. Currently, The Mousetrap is booking at London’s St. Martin’s Theatre (60th Anniversary trailer) until January 2015, “so the novella still hasn’t been published in the UK,” according to Listverse’s fascinating review: “20 Brilliant Novellas You Should Read.”

- The Third Man – Graham Greene – 1949 – written as preparation for the movie screenplay, a British film noir classic

- Breakfast at Tiffany’s – Truman Capote – 1958, the movie becoming more famous than the book and giving us “Moon River”

- Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde – Robert Louis Stevenson – 1886 – more than 120 film versions; about the recent musical, the less said the better

- The Time Machine – H.G. Wells – 1895 – feature film and television versions; inspiration for innumerable stories on this theme

- Of Mice and Men – John Steinbeck – 1927 – which Listverse anthropocentrically titles Of Men and Mice, has had numerous stage, film, and television versions

- A Christmas Carol – Charles Dickens – 1843 – staple of the holiday season in both film and stage versions.

So, how long should your book be?

Except for the Stephen Kings of the world, authors these days are expected to take a big hand (and perhaps the only hand) in the multiple activities of book promotion, even when the book has a commercial publisher. But that isn’t the end of it. Deciding to write a book presents the author with numerous chances for do-it-yourself consternation.

Except for the Stephen Kings of the world, authors these days are expected to take a big hand (and perhaps the only hand) in the multiple activities of book promotion, even when the book has a commercial publisher. But that isn’t the end of it. Deciding to write a book presents the author with numerous chances for do-it-yourself consternation. Martelle’s book also went through some cover re-designs to try to prompt the John Paul Jones connection. No dice. (J.P. looks a little bemused by all this, no?) At least Martelle had his publisher’s help with that. Authors who publish independently have to work out cover designs for themselves. Some hire a good designer and benefit greatly from it. Some go the DIY route, with predictable results. Some of their creations are at

Martelle’s book also went through some cover re-designs to try to prompt the John Paul Jones connection. No dice. (J.P. looks a little bemused by all this, no?) At least Martelle had his publisher’s help with that. Authors who publish independently have to work out cover designs for themselves. Some hire a good designer and benefit greatly from it. Some go the DIY route, with predictable results. Some of their creations are at  I took Book Drum for a test spin using one of my favorite books,

I took Book Drum for a test spin using one of my favorite books,  The fall 2013 issue of Glimmer Train includes an interview with short story writer and novelist

The fall 2013 issue of Glimmer Train includes an interview with short story writer and novelist  Starting to think seriously about my next vacation—only a few weeks away now—prompted by yet another flight detail change from United. The trip will start in Budapest, then float south along the Danube to Bucharest. On the journey, the boat will slip easily through the Iron Gate, the gorge separating Romania and the Carpathian Mountains on the north from Serbia and the Balkan mountain foothills on the south. Dams constructed over a 20-year period, ending in 1984, have turned what used to be a wild stretch of river into something more like a lake.

Starting to think seriously about my next vacation—only a few weeks away now—prompted by yet another flight detail change from United. The trip will start in Budapest, then float south along the Danube to Bucharest. On the journey, the boat will slip easily through the Iron Gate, the gorge separating Romania and the Carpathian Mountains on the north from Serbia and the Balkan mountain foothills on the south. Dams constructed over a 20-year period, ending in 1984, have turned what used to be a wild stretch of river into something more like a lake. Another feature of this trip is a three-day add-on excursion into Transylvania—ancestral home of my grandfather, who came from a tiny village annexed to the marginally larger village of Székelykeresztúr (“Holy Cross” in Hungarian) in 1926. Google maps gives the larger town no more than 12 streets. My grandfather’s home was about eight miles from the medieval walled town of Sighisoara, birthplace of Count Dracula. I have Transylvania roots, for sure.

Another feature of this trip is a three-day add-on excursion into Transylvania—ancestral home of my grandfather, who came from a tiny village annexed to the marginally larger village of Székelykeresztúr (“Holy Cross” in Hungarian) in 1926. Google maps gives the larger town no more than 12 streets. My grandfather’s home was about eight miles from the medieval walled town of Sighisoara, birthplace of Count Dracula. I have Transylvania roots, for sure.