James Franco as Jake Epping in 11.22.63 from Hulu

I’m excited about Hulu’s eight-part production (trailer) of Stephen King’s complex 2011 time-travel thriller, 11/22/63, which will premiere on President’s Day. I listened to the book several years ago and found it both gripping and fascinating. You may recall that, in King’s novel, high school English teacher Jake Epping goes back in time to try to thwart the assassination of JFK. Unfortunately, everything he does has rippling consequences he cannot foresee. It turns out that “history doesn’t want to change,” and to try to get it right, he has to reenter the past more than once.

There’s a mysterious character—the Yellow Card Man—who Jake finally learns is in charge of tracking the revisions in history he’s made and making sure all those events play out in their own new way. If someone’s life is saved, for example, they need a future, for better or ill—one they wouldn’t have had without Jake—and one that has its own infinite repercussions. I’ll let you see the series or read the book to get the full flavor of how tiny and profound those changes can be.

So here’s my Jake Epping experience. Consultation with the editor on my Rome-based novel led to agreement that several of the characters need to be expanded. Alas, the book was already straining publishers’ preferences at 98,000 words. Adding means subtracting.

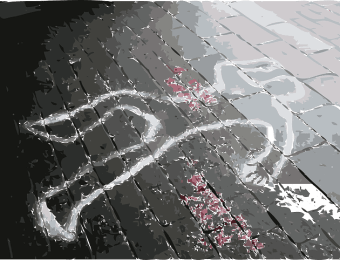

Now I’m working on a draft that will eliminate several characters. Like Jake, I’m taking them out of the story and revising the world I have envisioned. (If you’re a writer, too, you know how much time you spend in that alternative universe, filling it with people and objects and snatches of conversation!) All that has to be reimagined. While the roles of these late-lamented were more that of facilitating action, rather than major players, it’s still challenging.

Not only do I have to find plausible ways to get done the things these characters did (e.g., provide my main character with a place to stay; introduce her to the police detective who takes her case). It isn’t just a matter of changing names. In the way that you don’t talk to you best friend from high school the same way to talk to your boss (at least most of us don’t), the dynamics of the remaining characters’ interactions have to be adjusted.

Sometimes the whole point-of-view from which a scene is written must change. For example, a conversation in a cathedral is very different when seen from a priest’s point of view than from a criminal’s. Different speakers have different goals, different gestures and ways of speaking, and notice different things around them.

This isn’t a complaint. This process is energizing. You might say that the characters being eliminated were extra furniture, and I’m cleaning house. It’s sharpening my focus, too. Like Jake, I’m trying to understand a world made new. Though a few darlings have been killed in the process, I’m confident my book will be better for it!

A panel at last weekend’s Deadly Ink 2015 conference represented a spectrum of views about the research lengths mystery writers go to. At the “as factual as possible” end of the spectrum was K.B. Inglee, a writer of historical mysteries who is also a history museum docent and reenactor (talk about living your research!), closely followed by Kim Kash, who seeks a realistic recreation of Ocean City, Maryland, where her fictitious characters and stories play and play out. Setting her mysteries there began when she wrote a tour guide for the city, a compilation of facts and contacts that has since served her well.

A panel at last weekend’s Deadly Ink 2015 conference represented a spectrum of views about the research lengths mystery writers go to. At the “as factual as possible” end of the spectrum was K.B. Inglee, a writer of historical mysteries who is also a history museum docent and reenactor (talk about living your research!), closely followed by Kim Kash, who seeks a realistic recreation of Ocean City, Maryland, where her fictitious characters and stories play and play out. Setting her mysteries there began when she wrote a tour guide for the city, a compilation of facts and contacts that has since served her well.