You may have noticed that the book reviews on this website tend toward the positive. I decided a few months ago to post reviews here of only those books I could recommend. I’m choosy about what I read in the first place, but if a book doesn’t meet expectations, OK. What’s the point of giving a tepid review to a book that probably won’t ever come to the notice of most readers? Let those authors have their shot. Tastes differ.

Two books I’ve read lately are exceptions. Both are receiving a healthy dose of publicity—one because the author is popular and the other, a debut, because the publisher has put big bucks behind it. So these books may actually may attract your attention. Here’s what troubled me about them.

The Hollows

Mark Edwards is a popular British thriller writer. He set this story at a family camp in Maine—remote, wooded. A grisly double murder occurred there twenty years earlier, and the local teenager thought to have committed the crime disappears and isn’t seen again. When British journalist Tom and his teenage daughter arrive for a getaway, they learn right away about the killings and that many of the camp’s visitors are murder-porn tourists. Creepy events ensue. Is the place haunted, has the killer been living in the woods all this time, why are people warning them to leave? Of course, they don’t take any of this good advice (or there wouldn’t be a story), but Tom’s second-guessing and the predictable plot become tiresome.

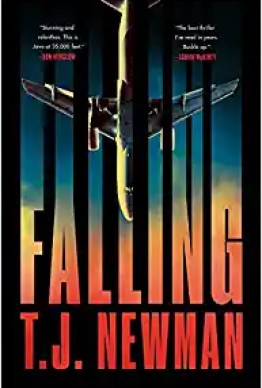

Falling

TJ Newman’s debut thriller is an exciting read, so much so (especially for us formerly-frequent flyers) that it may distract you from the plot’s implausibility. But after you close the book, the head-scratching will begin. Newman is a former flight attendant and captures the technical aspects of commercial flight very persuasively and her flight attendant characters are nicely three-dimensional. In a nutshell, a transcontinental passenger airline is hijacked and the pilot is told he must crash the plane when it reaches New York. If he refuses, his kidnapped wife and children will be killed. But aside from the behavioral clichés in the story, the bad guys’ plot is way way more complicated than it needed to be. Ultimately, it makes no sense. (I won’t say why in case you decide to give it a go.) There’s a lot of feel-good stuff near the end that doesn’t hold up either. This book has already been optioned for film and has Hollywood fakery written all over it.